Training a Reinforcement Learning Algo for the Math-Phobic

Below is a copy* of a talk I did at work about the Gymnasium side project. I didn’t talk about Queens at all, because I realized I only had 10 minutes, and teaching people how to play Queens and then explaining how I made a bot do it would take at least twice as long and isn’t relevant. (Also, as I’ll be posting about later, the queensbot is totally borked.) If you read my previous post on queensbot, you’ll see many of the same ideas here, but I think I did a good job of generalizing the content for a different audience, and so you may find this interesting as well.

I enjoyed giving this talk, although I was tweaking the slides up until the last minute, and next time I’ll try to manage my time a bit better/start earlier. That’s the pitfall of having a big event fairly quickly after winter break, and diving straight back into some pretty high-priority coding at the same time.

* It’s not an exact copy. I took out all references to proprietary information, for one, but also I’m working off my speaker notes, not the transcript. Also, I’ve had a few days to digest and have realized there are other, better ways I could have phrased things, so I’ve allowed myself to tweak here and there.

Training an RL algo for the math-phobic

Today I’ll be talking about how I trained a reinforcement learning as a math-phobic person. I used to be quite good at math but now I believe that I should let the computer do the math for me, and if you’re like me, you might also be intimidated by most forms of machine learning. I’m going to try to convince you to give RL a try, because unlike more complicated forms of ML, you can do it right on your laptop, and I found it to be a very good exercise.

But first, this is not what we’re going to be doing today.

Every time I Google “math behind AI” I get images that look like this, and this just makes me want to never play around with anything. But I swear this is doable, and it can be fun.

Why would I want to do this? For me, I want to be able to speak with some minimal amount of authority on machine learning, so that when my grandma says, “I heard AI is going to take over the universe and break down our component atoms into paperclips,” I can say, “Don’t worry, Grandma, there’s only a 4.5% chance of that happening.”

If you work on an ML team, or did ML in school, this stuff may be self-evident, but for me, there’s a vast gulf between knowing instinctively that “AI is just math” and actually seeing it in action. So I wanted to know more about how we make computers ‘think’, big emphasis on the air quotes, and the best way to do that is to try to do it yourself.

So this is Wikipedia’s definition of reinforcement learning. It’s also kind of a lot. Let’s call it, a way to train an AI to do something, through conditioning. If it does a good thing, we reward it, and if it does something bad, we punish it. It’s like training a puppy. This is about the most math we’ll need today.

So as you can see from the diagram, we need two things: an agent, which is represented by the robot, and an environment or game, which today will be tic-tac-toe.

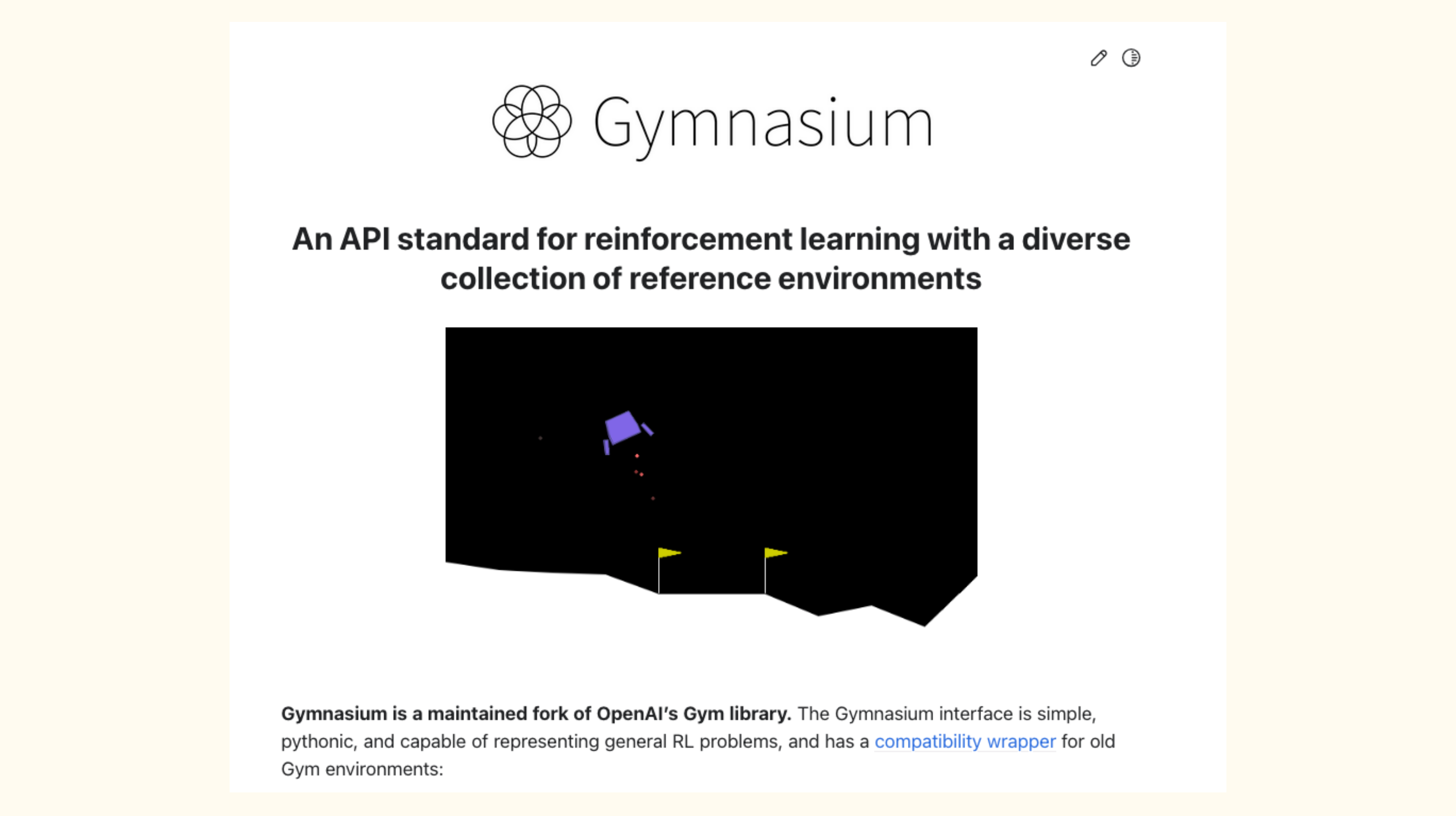

Gymnasium is the most popular library for creating an environment. It used to be maintained by OpenAI, but they got busy with something or other, and so now it’s maintained by a nonprofit. You don’t need Gymnasium to do RL - you can do it with raw python - but this library makes your game into a consistent format, it comes with some pre-built environments, which I’ll talk about later, and it has decent documentation and tutorials, and those are all pluses. You’re seeing a screenshot here of Lunar Lander, which is one of the pre-built environments built into Gym, but today we’re going to be building our own environment. That’s pretty simple:

class TicTacToeEnv(gymnasium.Env):

metadata = {'render.modes': ['human', 'rgb_array']}

def __init__(self):

super(gymnasium.Env, self).__init__()

self.board = np.array([['-', '-', '-'],

['-', '-', '-'],

['-', '-', '-']])

self.action_space = DiscreteWrapper(9)

self.players = ['X', 'O']

self.num_players = 2

self.current_player = 'X'

def step(self, action):

win = False

lose = False

y = int(action / 3)

x = action % 3

self.board[y][x] = self.current_player

game_over, winner = self.is_game_over()

if winner == self.current_player:

win = True

reward = 1

elif winner == "draw":

reward = 0

lose = True

else:

lose = True

reward = -1

return self.board, reward, win, lose, {}

def reset(self, seed=None, options=None):

self.board = np.array([['-', '-', '-'],

['-', '-', '-'],

['-', '-', '-']])

self.info = {}

self.action_space=DiscreteWrapper(9)

return self.board, self.info

This is a tic-tac-toe environment in basically 30 lines of code. We just need to be able to initialize the game, take actions and get feedback, and reset the game after a win or loss.

The actual logic of tic-tac-toe is not included here, but in this example we’re assuming you have a game built and just want to encapsulate it in a gym environment for RL.

So now we need an agent. I chose Q-learning based on vibes, and also because it’s one of the simpler algos out there, and there are lots of other examples you can copy learn from.

But also when you search for Q-learning tutorials you get a video that looks like this:

This is the intro and it doesn’t get less confusing. So again, let’s simplify and say that Q-learning is basically a big table.

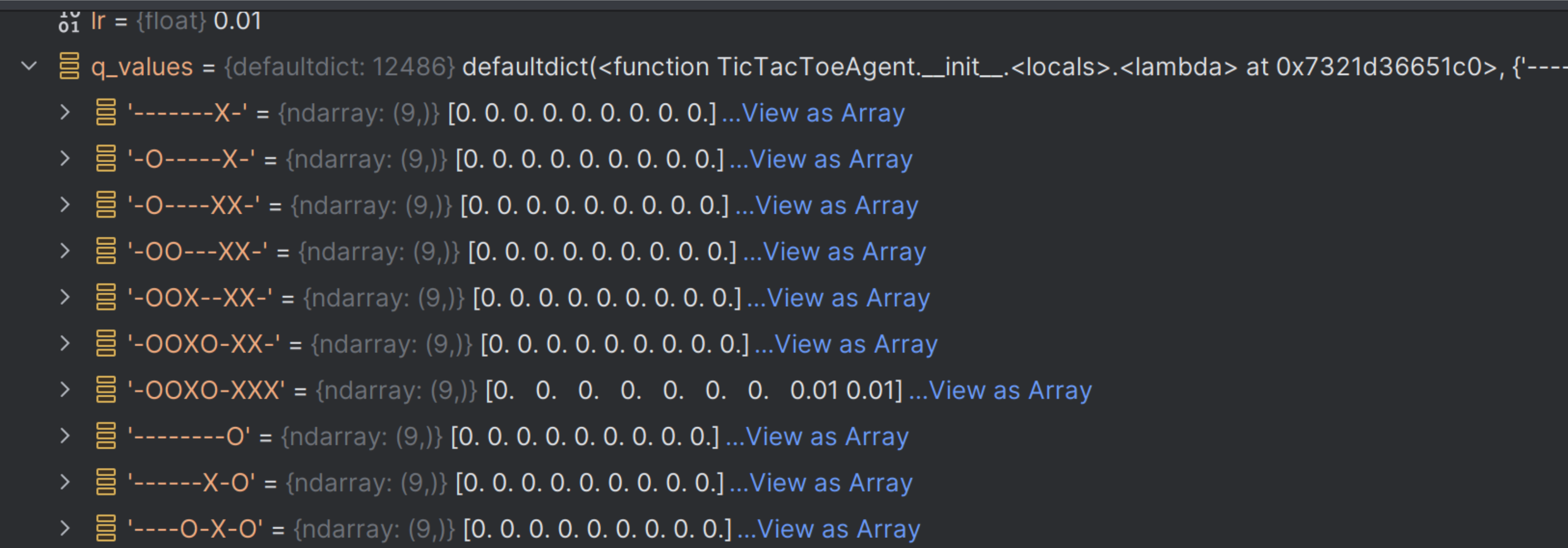

In this case it’s a dict, but same deal. The keys of the dict are possible game states, where a tic-tac-toe board is represented as a 9-character string of Xes, Os and blanks. The values of the dict represent the 9 possible actions for each state. And the agent is just going to store numbers in those lists representing the predicted reward of taking action X given state Y.

So the agent starts by taking actions at random and updating the Q-table based on the outcome. The actual value that’s put into the table does involve math, which we’re not going to go into, but the gist of it is the math accounts for future rewards. So if you’ve played tic-tac-toe before, you know that starting in a corner is usually a good winning strategy, but you also know that you can never win tic-tac-toe in one move. So we need magic math to tell the robot that a corner start is a good strategy even if there’s no short-term payoff.

So the agent goes along taking random actions and updating its table. And as we go along we have this value called epsilon, just by convention because epsilon usually refers to small numbers. And epsilon starts at 1.0, and this is basically the whole “brain” of the robot, to put it poorly.

# with probability epsilon return a random action to explore the environment

if np.random.random() < self.epsilon:

return self.env.action_space.sample()

# with probability (1 - epsilon) act greedily (exploit)

else:

return int(np.argmax(self.q_values[obs]))

For each action, we get a random float between 0 and 1. If it’s smaller than epsilon, which it usually is at the beginning of a session, we take a random action and update the Q-table. At the end of each game, the epsilon value shrinks by some tiny amount. So at some point it’s more probable that epsilon will be smaller than our random number. And at that point all the agent does is look in the Q-table, find the action with the highest probability of a reward, and take it. That’s it, that’s the math.

Here’s a non-live demo of a tic-tac-toe agent playing 50,000 games against itself, and winning 87 percent of the time.

Wow, that was really boring to watch.

Well, it might have been boring to watch, but I hope I’ve convinced you to give RL a try and that the math isn’t scary.

But let’s talk about pitfalls, because I did all of them.

First of all, do test any of your game logic. It may seem silly to write “assert three X’s equals winning game” but it’s hard enough to find bugs in your code when you’re running it yourself. It’s even more difficult to discover any logical errors when the code is running in basically a black box. So these tests will save you time in the long run.

Also do start with something like tic-tac-toe. My first attempt at this was to solve a puzzle with 64 possible moves, 96 win states, and something like eleventy kabillion possible game states, which is a little much.

Do feel free to use gym.make(). That allows you to - in a single line of code - skip the custom environment and use one of the premade environments I mentioned earlier. Then you can get right to the RL without having to worry about game logic.

Also, do visualize your output. That will help you make sure your algorithm isn’t engaging in “specification gaming,” which is essentially malicious compliance for RL. For example, if you’re training an algorithm to beat Mario, you might set the goal condition as “get as far to the right as possible and don’t die.” However, if you’re a RL algo…

If you just stay in one place and hop up and down, you don’t die. Mission accomplished?

Or here’s a robot that was given the goal to stack the red lego on top of the blue lego, but the way this was implemented was “the reward is equal to the height of the bottom edge of the red block when the robot arm is not touching the block.”

As you can see it’s significantly easier to just flip the red block over than to bother to learn to stack, and the reward is almost as good, if not equal.

So you really have to be careful that what you’re measuring is actually the outcome you want.

Cool, have fun! Good luck! Don’t program an evil AI to take over the world please kthxbai!

-fin-