Teaching a Reinforcement Learning Algo to Play Queens

Once you have created infinite games of Queens, you need to play infinite games of Queens. I don’t have time for that, so the next logical step is to teach the computer how to play, taking humans out of the equation entirely.

A very cool data scientist I know recommended getting to know reinforcement learning algorithms. These are the AIs that do cool things like speedrun Mario. Why not train one to beat Queens? Why not, indeed. Ignoring the part where I have no experience in machine learning and don’t think much of my math skills (I was a middle school mathlete, but I still don’t think much of my math skills), this should be fun. Follow along with me as I take my first steps into machine learning.

Confession: The first draft of this post was written nearly a month ago. I went down so many blind alleys that I thought would take me somewhere, but they did not. Reader, there were tears.

I have basically skipped over all the hard parts and blind alleys, not because they are embarrassing, but because they are uninteresting. If you are interested in knowing where I went wrong, I’ve listed a few of them at the end of this post.

What I eventually determined is that to accomplish my goal (“train a robot to play the game I built”) I need two, or maybe three things. An environment (the game) and an agent (the thing that ‘learns’ how to play the game). The agent learns how to play the game by taking various actions (place a queen) and seeing what happens to the state of the game. We give the agent various rewards: big rewards for good moves, negative rewards for bad moves.

In our Mario example from before, Bowser could be giving Mario a coin every time he makes it further in the level, and taking them all away (and clubbing him over the head) every time he touches a Goomba. Going forward good, dying bad.

The maybe-third thing we need is some way to visualize the agent’s progress, and we’ll get to that later. First, let’s tackle the environment.

I chose (was recommended to choose) the gymnasium library to create my environment. This library comes with a bunch of example environments (the game/puzzle/etc being played) to experiment with, but I am going to create a custom environment by subclassing gymnasium.Env.

class QueensEnv(gymnasium.Env):

metadata = {'render.modes': ['human']}

def __init__(self, size):

super(gymnasium.Env, self).__init__()

self.game = np.zeros(shape=(8,8))

self.action_space = spaces.Discrete(64,)

The above code initializes an 8x8 2d array of all zeros to represent an empty chessboard. It also defines the “action space” of the agent. In this case, the action space is discrete (an un-quantifiable action, as opposed to a continuous action). Each action corresponds to a space on the board: action 1 would place a queen in the upper left corner, and action 64 would place a queen in the lower right.

Then we have to implement a couple methods: step and reset.

reset simply sets the game back to zero so the agent can try again.

step is slightly more complex. It represents each tick of the clock. Each step, the agent will take a single action, and step will return the new state of the game as well as the rewards (if any) the agent has received.

def step(self, action):

win = False

x = int(action/self.length)

y = action % self.length

self.game[y,x]=1 #note, numpy syntax is weird :D

reward, win, lose, info = get_points(self.game, self.length)

return self.game,reward,win, lose, info

get_points is a separate function I defined to calculate a few things:

- is the board “valid”? (If so, increase the reward; if not, end early by setting

losetoTrue.) - is the game complete? (If so, increase the reward by a lot, and set

wintoTrue.)

We also need to define a render function. This can be done with something like pygame but I’m just going to print my board to the console for now:

def render(self, mode='human', close=False):

print(self.game)

print(" ") #empty line between boards

It isn’t pretty, but it works.

We now have everything we need to run our environment. But now we need an agent.

This is the part where I’m really in over my head. The math is mathier here: I watched a Youtube video that included the mathematical notation  . Yeesh.

. Yeesh.

I admit I pretty much wholesale lifted Farama’s blackjack Q-learning agent code for this part, but getting it to run on my code was still its own challenge.

The broad strokes of Q-learning are that your agent builds a table that contains all possible states of the game, and all possible outcomes (rewards) based on each action. In other words, if the game looks like X and I do Y, what is the probability that Z will happen?

From that, it can either take random actions (to continue to build out the table of probabilities) or choose the action that has the highest probability of being the best move. It’s much less like a chatGPT type algorithm and much more like a Markov chain.

Once I understood all that we were golden. A reference table is basically a python dict, and I can see a few places in the Gymnasium agent code that look like it’s referencing a dict where the state of the board is the key: return int(np.argmax(self.q_values[obs])) for example.

The only reason this didn’t work for me off the bat is because my observation (the state of my game) is a numpy 2d array, which cannot be used as a dict key. If I do this, however:

return int(np.argmax(self.q_values[tuple(np.ndarray.flatten(obs))]))

now my array becomes a “hashable type” (can be used as a dict key).

I did not write much other code for the agent. The base code can be viewed here. Essentially, we need two functions: one to choose an action (either randomly or from the q_values table) and one to update the q_values table once we have an outcome.

The math involved in terms of deciding what the actual value of the action is is a bit complex, it’s not just the reward – it is calculated based on the value of the reward plus predicted future rewards if the agent continues. But the math on deciding whether to pick a specific action rather than taking a random one is basically: if a random number is less than epsilon, choose randomly – and epsilon gets smaller and smaller each run of the game.

This is a lot more coding and a lot more yakking than I normally write. But we’re in the home stretch! The last thing we need is a way to visualize the model’s output. Again, I borrowed this from Farama Foundation, with some special fun since I run Linux at home these days. (TLDR: To use matplotlib on Ubuntu-based systems, make sure to install libxcb-cursor0 if you haven’t already.)

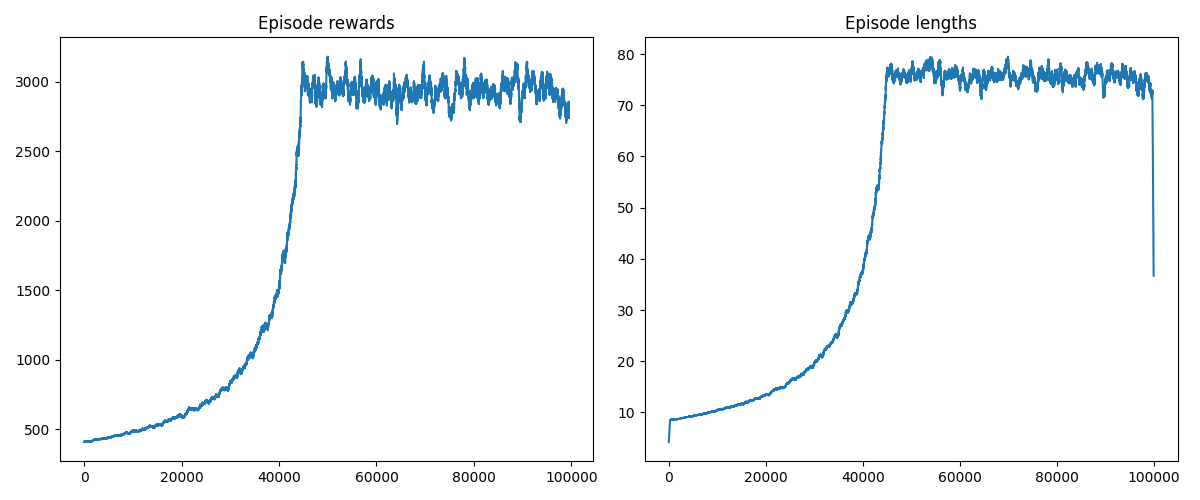

And with that, we can run our agent for a few minutes and get results:

The rewards max out after about 40,000 episodes, as does episode length (as it should; making it to an episode with 8 steps pretty much guarantees success). I’m not sure what’s going on at the far right of the second graph, but I’m willing to chalk it up as a data error.

So we have now proven that a RL algorithm can learn to solve the 8-queens problem. What I really want, of course, is to watch it solve the game, which is less exciting when the “game” consists of ones and zeroes in a terminal. So next steps are to render the game (using pyGame?) so there’s something more interesting to watch. But I’ll have to save that for a future post, as this is already 1500 words long.

In the meantime, my source code is available on Github.

Dumb mistakes I made while building this

- Building an “action space” that required the agent to traverse the board, rather than be able to place queens anywhere. This was too complex and didn’t go anywhere.

- Not realizing, for a very long time, that

gymnasiumonly provides the environment, and the agent has to come from elsewhere. - Messing with my points method without writing unit tests first. Once I had a set of incredibly basic tests, changing the rewards or refactoring the code was stupid easy.

- Starting with the 8-queens problem. The smallest possible board that can be solved with this type of puzzle is a 4x4, and you can imagine that an action space with 16 options is significantly faster to iterate over than an action space with 64 options. I eventually modularized my environment so the agent should be able to solve Queens problems of any size.