Composing Functions in Python

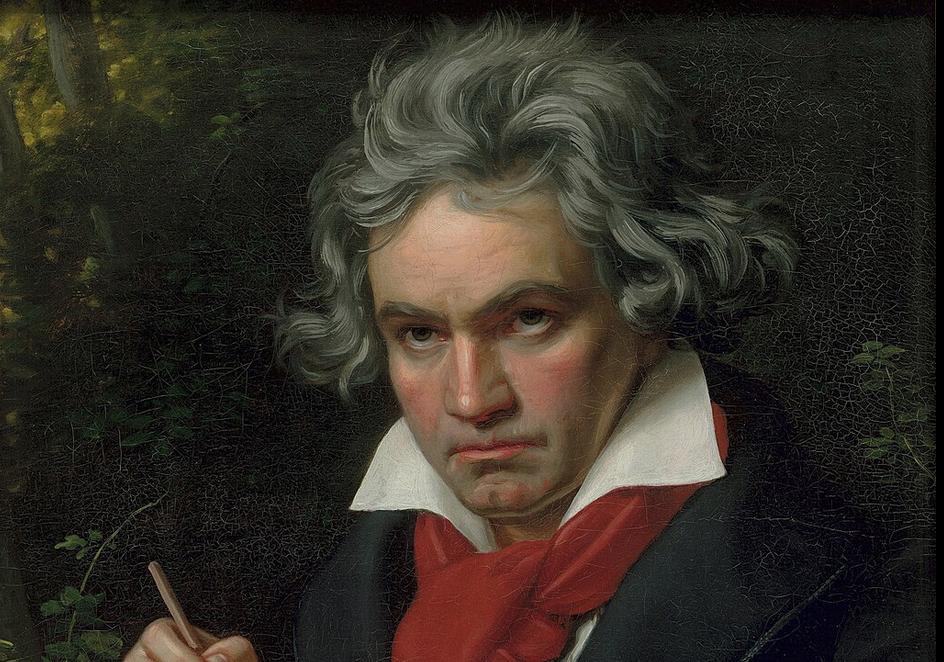

Beethoven did not compose any functions, that I know of.

Beethoven did not compose any functions, that I know of.

I have not done a lot of functional programming, although someone I used to volunteer with was very into it. This weekend, while attempting to solve Advent of Code, I came back across some functional techniques.

I probably should have solved the day’s puzzle (a variation on the missing operators puzzle) with these tools. (Did I? Reader, I did not - I concatenated a giant string and then eval()ed it. I am a massive hack.) But let’s talk about composing functions, because I think it’ll be useful someday.

What does it mean to compose a function?

Composing functions does not have anything to do with writing music. It simply means to create a function that returns another function as its result. (I have also heard this described as a higher-order function.)

So if you have:

def square(x):

return x*x

def add_one(x):

return x+1

The normal way of invoking both of these functions might be:

x=2

x=square(x) #x is now 4

x=add_one(x) #x is now 5

But using composability, we could:

def compose(*fns):

return functools.reduce(lambda func1, func2: lambda x: (func2(func1(x))), fns)

square_and_add_one=compose(square,add_one)

square_and_add_one(2) #result is 5

If this looks like witchcraft to you, it also did to me at first. Let’s break down what’s going on in compose.

compose takes one parameter, fns, which is prefixed by the splat operator, which means we unpack each item passed to it into a list. (Similar-ish to ...spread syntax in Javascript). Then we use the reduce function on the list.

I’m much more familiar with a reducer from math operations. For example, if you have [1,2,3,4,5] and want to know the product of 1*2*3*4*5, you can write:

nums=[1,2,3,4,5]

result = functools.reduce(lambda acc, num: num*acc, nums)

Or in other words, for every item in nums, multiply it by the accumulated (reduced) result.

1*2=2

2*3=6

6*4=24

24*5=120

Our compose reducer does the same thing, but instead of performing a multiply operation, it returns a new function whose function is to call the previous function.

So if we do square_and_add_one=compose(square,add_one) the result is a function that first squares its input, then adds one to it. It would be the equivalent of: add_one(square(x))

Cool. Why do we care?

I initially thought I could solve the Advent of Code puzzle by composing functions. As I said, the puzzle was essentially the following:

Given the numbers (for example) 81, 40, and 27, what combination of multiplication and addition will create the desired total, in this case 3267?

With three numbers and only two possible operators, this is easy enough to brute force by hand, but of course the real challenge has 10+ digits in each line. I was hoping that I could get every combination of length n of the two operators (e.g. "+,+,+,+,+,+,+,+,+,+","+,*,+,+,+,+,+,+,+,+", and so on) and toss those into a compose, and see what popped out.

This did not work for a number of reasons. One, because if you want your composed functions to take more than one parameter, you have to do some fancy work.

Two, and this is more important, I don’t actually want to do add(multiply(81,40,27)). What I want is add(multiply(add(81,40),27)) and that subtle distinction is actually quite a big difference. I won’t say there isn’t a way to get that result with composing functions, because there is almost certainly a way to do everything, every way, in code. But by that point I’d been hacking away at the problem for a bit and I decided to just make a silly naive solution.

I also think that unless you’re very careful, composing functions can lead to abstractions that are hard to read and debug, as cool as they look.

I am not sure I will be making heavy use of this technique in my own work but I’m glad to have messed around with it, if only to recognize this pattern when I see it in the wild.